Trust in Transition #21

Building Trust Infrastructures

Welcome to the October 2025 edition of Trust in Transition. This monthly newsletter, compiled by WISER scholars, is your gateway into finance, technology, and trust in Africa. Each month, the Substack features WiSER scholars unpacking the current events and stories shaping their research.

Inside This Edition

🗓️ September Recap

🌍 WiSER on the Move

⭐ The WiSER Feature: “Building Trust Infrastructures: The Power of Community Trusts in Africa’s Development” by Raymond Onuoha | Postdoc Fellow | Trust

✏️ Contributions:

In this edition, Wiser Trust scholars and affiliates are reading the following:

“Gold and Geopolitical Trust” Keith Breckenridge | Professor | Trust

“Cyber Resilience and State Capacity in West Africa: Lessons from the DDoS Surge” Hannah Krienke | Doctoral Fellow | Trust

“Gambling in South Africa” Laura Phillips | Senior Researcher | Trust

“In Gold we Trust: Gold breaks the $4000 barrier” Tunde Okunoye | Doctoral Fellow | Trust

“Ghana’s National Service Authority (NSA) is in the spotlight again” Caroline King | Doctoral Fellow | Trust

“What IMF Debt Really Measures” Fatima Moolla | Doctoral Fellow | Trust

“Legal Identity Across the Life Course: Gender, Registration, and the Politics of Digital Inclusion” Jonathan Klaaren | Professor | Law

This month’s edition of Trust in Transition traces how power travels through systems. We look at gold as a hedge against geopolitical pressure, cyber attacks as stress tests of state capacity, and digital IDs as sites of both inclusion and exclusion. We follow community trusts in Southern Africa, where local ownership of infrastructure is being used to build legitimacy from below. And we return to the question that sits underneath it all: who is trusted to govern money, identity, and infrastructure in Africa — and on whose terms?

The Trust Seminar

The September edition of the Trust Seminar Series brought together a set of interdisciplinary conversations on law, technology, and governance — exploring how trust is shaped and strained across political, economic, and digital systems.

Sara Dezalay opened the month with “Socio-Legal Enquiry on a Global Scale: Legal Intermediation, the Geography of Extraction, and the (Re)Negotiation of Africa’s Relationship with the World Economy.” Her presentation examined how law mediates the global green transition, tracing the ties between legal regimes, extraction, and finance. Drawing from her new book Lawyering Imperial Encounters, Dezalay unpacked how these dynamics reproduce Africa’s subaltern position in the global economy.

In “When the State Always Doubts Your Identity,” Nayanika Mathur and Tarangini Sriraman turned to the Indian state’s efforts to classify and verify its citizens. Moving beyond narratives of document scarcity, they revealed how bureaucratic practices like the Special Intensive Revision (SIR) and National Register of Citizenship (NRC) embody a deeper politics of “impossible identification,” exposing the tension between inclusion and surveillance.

Marielle Debos followed with “The Biometric Promise: Technology, Market, and Elections in Africa.” Based on multi-sited fieldwork, Debos traced the rise of biometric voting systems across the continent, showing how a technology once promoted as a cure for electoral fraud has evolved into a complex political instrument. Her talk illuminated how vendors, donors, and African political elites together shape the technopolitics of democracy.

Concluding the month, Tunde Okunoye presented “Understanding Digital Public Infrastructure (DPI) through Nigeria’s NIBSS NIP Real-Time Payments Layer.” Okunoye explored how real-time payments have transformed financial inclusion in Nigeria, positioning the NIP as the payments layer of the country’s broader DPI ecosystem. He argued that trust in such systems is constructed “from the top down,” through the credibility of central banking and regulatory institutions.

Together, these seminars advanced the Trust theme’s core concern: how infrastructures — legal, technological, and institutional — organize power, mediate trust, and shape the contours of governance across the Global South.

WISER's TRUST seminar is hosted on-line every Monday afternoon at 16:00 - 17:00 SAST during the teaching semester. Forthcoming seminars are available here, and past events are detailed in our archive.

WiSER on the Move🌍

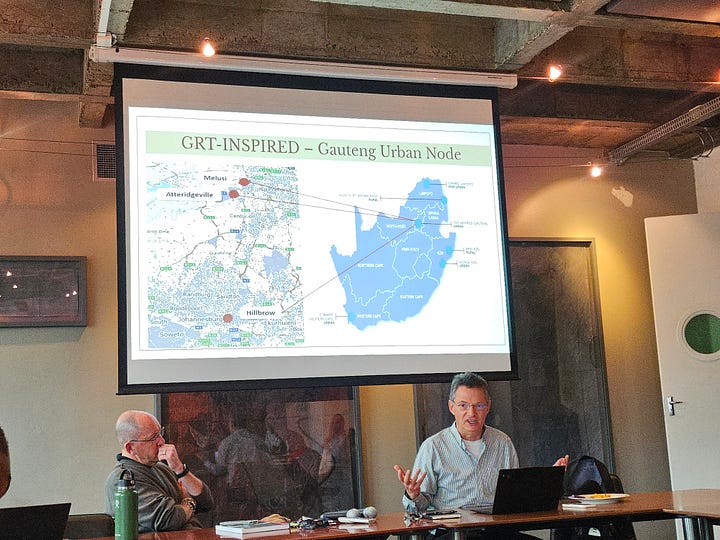

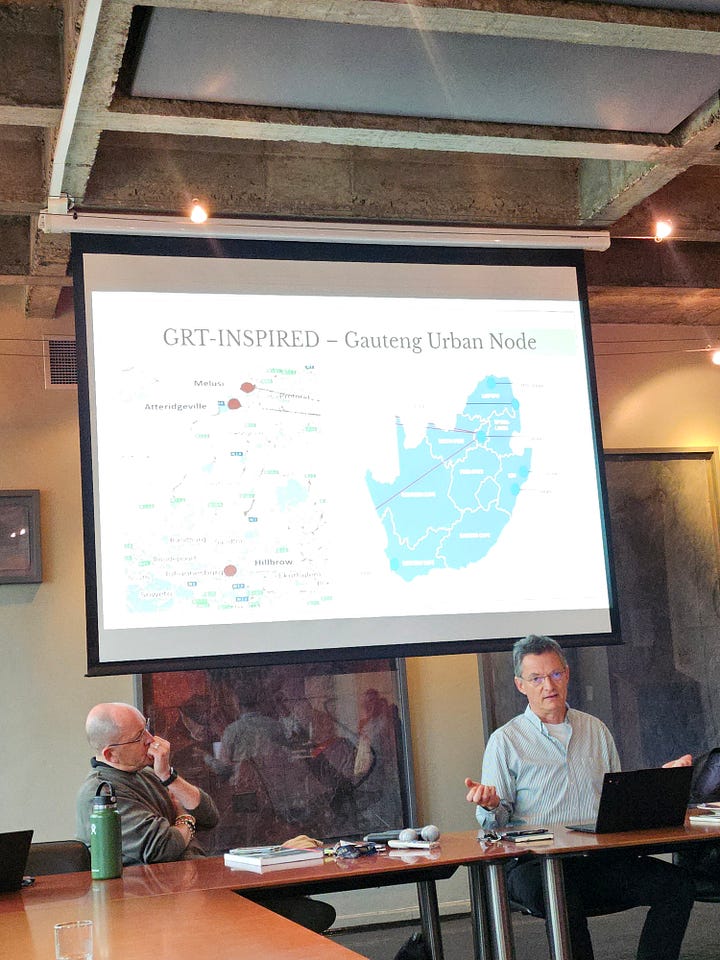

Keith Breckenridge participated in the Interdisciplinary ‘Conversations on Water’ series at the WiSER. Breckenridge presented a talk titled “Rethinking the Curse of Mine-Financed Urban Infrastructures” alongside David Everatt, who spoke on “Death by Water in Hillbrow.” The discussion formed part of an ongoing series co-convened by Craig Sheridan and Sarah Nuttall, exploring water, infrastructures, and governance in Johannesburg.

Doctoral Fellow, Caroline King participated and attended the two day Nkabom Project Workshop at the Department of Geography and Resource Development at the University of Ghana. Michaël Bourdon and Caroline King presented a preliminary research paper, tentatively titled: “FinTech Everywhere and Nowhere: Financial Inclusion from Above and Below in Ghana”.

Caroline King has also been conducting parts of her on-going field research in a rural part of Ghana’s Eastern Region over the past month. During this time she conducted interviews with mobile money users in a town that does not have access to state or banking infrastructures. She also interviewed and observed various mobile money agents in the town.

Janaina Costa, Fellow with the IUSSP/IDRC Panel, led a ‘world café’ session on Digital Public Infrastructure (DPI) and the UNDP Safeguards at the Nairobi Expert Group Meeting. Members of the IUSSP/IDRC Panel on Population Registers, Ethics, and Human Rights also met in preparation for the upcoming Expert Group Meeting, to be held on 13–14 October 2025 in Nairobi, on “Consolidating Lessons from the Field and Synthesizing International Technical Standards on Population Registers and Their Usability.”

WiSER Trust members attended the launch of Nontsizi Mgqwetho: The Poet of the People (1919–1929) by Thulani Mkhize, hosted by UKZN Press in collaboration with the WiSER. The author was in conversation with Professor Isabel Hofmeyr, exploring Mgqwetho’s poetic call for Africans to reclaim a sense of self and nation disrupted by colonialism — a vision that continues to resonate more than a century later.

The WiSER Feature 📝

“Building Trust Infrastructures: The Power of Community Trusts in Africa’s Development”

by Raymond Onuoha | Postdoc Fellow | Trust

Community trusts—legally constituted bodies that manage assets on behalf of a community—are emerging as a foundational “trust infrastructure” across the globe (Leat, 2004). By design, community trusts ensure that a share of the benefits from large infrastructural projects flows directly back to local residents. For example, in South Africa’s Renewable Energy Independent Power Producer Procurement (REIPPPP) programme, independent community trusts must receive a portion of project profits. This guarantees that when a solar or wind farm is built, nearby communities literally “share in the energy”. In theory, these trusts bridge the gap between projects and people: they can actively engage local voices in planning, manage resources for community needs, and reinvest revenues into everything from water and telecommunication networks to schools and training programs. In this way, community trusts do more than deliver services—when they work properly, they build trust between citizens, companies, and governments by showing that infrastructure projects are about community upliftment as well as profit.

Key Roles of Community Trusts

Community trusts contribute to development in multiple, interlocking ways:

Benefit-Sharing: Trusts ensure communities reap direct rewards from projects. By law (for example in South Africa’s REIPPPP), a portion of revenues is set aside for a community trust. These funds are then allocated for the community’s priorities. Such built-in benefit-sharing demonstrates that the project is not just about profit but also about community upliftment.

Local Economic Development: Revenue in community trusts is invested in local enterprises, skills training, and infrastructure projects. This approach means communities do not passively wait for trickle-down effects, but actively participate in the positive impact. It fosters a sense of ownership and shared responsibility as tangible benefits – like new roads, water systems, or small-business grants – are powered by the project’s profits.

Capacity Building and Empowerment: Trusts often fund leadership development and training for community members. By building local capacity—helping young people and marginalized groups learn governance and technical skills—trusts ensure community members have a strong voice in decision-making. This investment in human capital deepens trust by demonstrating an inclusive commitment as trustees can invest in building local capacity and strengthening leadership at the local level.

Strengthening Governance: Community trusts work hand-in-hand with local government and traditional structures to improve accountability. They require the trust’s own administration to follow clear rules, and they encourage transparent reporting to beneficiaries. In doing so, trusts model the kind of inclusive, accountable governance that builds confidence in institutions.

Social Impact Partnerships: Beyond infrastructure, trusts foster broad social benefits. They can channel funds into education, healthcare, and food security projects by partnering with community groups and NGOs. For instance, community trusts have financed local scholarship programs, early childhood learning centers, and health clinics where they were needed. By aligning multiple stakeholders (residents, funders, government) around shared goals, trusts help create a stronger, more resilient social fabric.

Examples and Evidence from the Field

The impact of community trusts can be seen in both data and real-world stories. A study of Cameroon highlights the power of delivering tangible infrastructure in building trust. Cameroonians surveyed as part of an Afrobarometer study overwhelmingly credited local infrastructure—electricity, water, schools, roads—with increasing their trust in government representatives. In fact, the researchers found that for each unit improvement in a community’s infrastructure index, the likelihood of citizens trusting their local officials jumped by roughly 50%. In other words, when people see a new clinic or reliable power in their village, they reward leaders with trust. This “bottom-up” accountability is crucial, especially in settings where national politics may feel distant. It tells us that investing in community-level infrastructure—precisely what community trusts enable—can directly foster political legitimacy and citizen confidence.

Another concrete success story comes from South Africa’s renewable energy sector. In the Free State province, the Letsatsi Solar Park Community Trust has taken solar power revenue and turned it into brighter futures for children. Since 2023, the trust has backed an after-school literacy program called Otsile Bokamoso (“the future is bright”). It funded classroom equipment, tutoring materials, and teacher training, and even helped with branding and marketing for the program (Mochoari et al., 2025). This support has dramatically improved reading outcomes: over 2,000 young learners have benefited, and school dropout rates have fallen. As the program’s founder notes, “We now have children who read to understand and because of what we are doing... their future is bright”. This example illustrates the multiplier effect: a renewable energy project generates electricity (and profits) for the grid, and a community trust turns some of that profit into social programs. In this case, installing solar panels ultimately puts books in children’s hands. Such stories make it clear that community trusts can translate renewable energy and other infrastructure into tangible community upliftment.

Other African countries are also exploring this model. Banks and development institutions (like the Development Bank of Southern Africa, DBSA) are increasingly involved in setting up and financing community trusts alongside large projects. The DBSA itself notes that when properly supported, community trusts create jobs and advance a just energy transition, but they must be backed by robust governance and oversight. These observations reinforce that community trusts are most effective when they operate transparently and inclusively.

Governance, Sustainability, and Legal Challenges

Despite their promise, community trusts face significant hurdles. The governance of a trust must be carefully managed: boards of trustees need balanced representation, integrity, and relevant expertise (Dartington, 2005). Poor leadership or conflicts of interest can erode trust rather than build it. Funding and sustainability are also concerns: trusts must have reliable long-term revenue and must be able to deploy those funds effectively (Bingham & Walters, 2013). Without ongoing capital and strong management, even well-intentioned trusts can falter. Furthermore, legal and regulatory frameworks vary by country. In some places, the law around communal ownership and trusts is unclear or outdated. For example, South Africa’s Trust Property Control Act of 1988 provides guidance, but other African countries (where the English equitable tradition of trust law applies in theory) may need updated legislation to govern community trusts effectively.

Effective community engagement is another critical challenge. Trusts must continually involve beneficiaries in decision-making; otherwise, resentment can build. Regular communication and transparency are essential. As one community trust advisor explains, open feedback loops and clear conflict-resolution rules (built into the trust deed) are key to avoiding tensions. For instance, a trust should have a public five-year plan, so different villages know when to expect their turn for funding, preventing suspicion about “who is left out”.

Finally, even with all structures in place, ensuring that trusts address real community needs requires discipline (Roberts, 2024). Policymakers and investors must guard against duplication of government services. Before a trust launches a project, it should conduct a socio-economic needs assessment in the community. If, say, government programs already cover school meals, but the village lacks clean water, the trust should focus on water pumps instead of repeating school feeding. This needs-driven approach keeps the trust relevant and avoids wasted resources.

Policy Recommendations

To unlock the full potential of community trusts, strategic support is needed from both policymakers and investors:

Enact and Enforce Benefit-Sharing Policies: Governments should mandate that infrastructure projects include community trust arrangements. The South African REIPPPP model is a clear example: renewable energy contracts require community shares. Other African countries can adopt similar rules across sectors (energy, mining, telecom, digital infrastructure, etc.) to institutionalize benefit-sharing and build trust from the outset.

Strengthen Legal Frameworks: Lawmakers should clarify and update trust laws. Legislation like the Trust Property Control Act in South Africa offers a template, but countries should ensure laws define how community trusts are formed, how trustees are selected, and how funds must be managed. Clear legal guidance reduces uncertainty and increases investor confidence that their community partners are properly structured.

Build Trustee Capacity: Public and private funders must invest in training for trustees. Workshops on financial management, governance, and community liaison can ensure trustees can fulfill their roles effectively. For example, requiring a certain level of education or expertise (or offering bridging education) for board members can professionalize trust management. Well-equipped trustees are better at planning and less likely to make mistakes that erode trust.

Mandate Diversity and Accountability: Governance rules should require diverse trustee representation (including women and youth) to reflect community demographics. Independent audit and reporting standards—possibly overseen by development banks or regulators—will promote transparency. This counters “elite capture” and corruption, challenges that can derail even well-funded trusts.

Invest in Community Outreach: Both governments and investors should support ongoing community engagement. This means funding outreach coordinators or communication campaigns, and establishing grievance mechanisms. According to practitioners, frequent and transparent communication is the best way to defuse tensions and build ownership. Structured community forums (e.g. quarterly meetings) allow residents to track how trust funds are used and voice concerns early.

Align with Community Needs: Before investing, conduct a community needs assessment. Investors should focus on the nearest communities (e.g. within a 5–10 km radius of a project) and work with those communities to identify priorities. This proximity principle not only makes monitoring impact easier, but also ensures the trust serves those most affected by the project. In practice, communities should also be encouraged to identify their own development opportunities and seek investor partnerships proactively.

Leverage Development Finance: Development banks like DBSA can play an active facilitation role. By providing early-stage grants and oversight, they can help establish best-practice governance in new trusts. These institutions should make funding conditional on clear benefit-sharing plans and robust accountability measures. Such involvement can also help secure long-term financing (for instance, trust endowments) so that community projects remain viable for decades.

Promote Knowledge Sharing: Finally, regional bodies and academic institutions should document success stories and models of community trusts across Africa. Policymakers can then learn from peers (e.g. how Uganda might adapt South African lessons) and continuously refine their approaches. Sharing data and lessons will build momentum for trusts as a proven model of inclusive infrastructure.

By taking these steps, African governments and investors will not only improve the sustainability of infrastructure projects, but also strengthen the social fabric. As one expert puts it, community trusts should not be an afterthought but a “foundational element” of development strategy.

References

Bingham, T., & Walters, G. (2013). Financial sustainability within UK charities: Community sport trusts and corporate social responsibility partnerships. VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, 24, 606-629.

Dartington, T. (2005). Trustees, committees and boards. In Introduction to the Voluntary Sector (pp. 219-234). Routledge.

Leat, D. (2004). The development of community foundations in Australia-recreating the American dream. Australian Centre of Philanthropy and Nonprofit Studies. https://eprints.qut.edu.au/69030/1/cpns_book_SPV.pdf

Mochoari, R., Molelekwa, T., & Mofokeng, M. (2025). Community trusts are greening the future. https://oxpeckers.org/2025/03/community-trusts/#:~:text=She%20set%20up%20Otsile%20Bokamoso,Bokamoso%E2%80%99s%20branding%20and%20marketing%20efforts

Roberts, S. (2024). Rebuilding Trust in a Divided Community: An Integrated Approach. Pepp. Disp. Resol. LJ, 24, 461.

✏️ Contributions:

“Gold and Geopolitical Trust”

Odd Lots interview with Raghurum Rajan, former Governor of the Reserve Bank of India

Submitted by Keith Breckenridge | Professor | Trust

As Wiser PhD Fellow Tunde Okunoye notes below, the price of gold has been surging over the last few months, and in this interview, the former RBI chief points to the geopolitical struggles over SWIFT and the expropriation of central banks’ foreign currency assets as the main cause of the turn to gold. Demand for the metal, now expanding through ETFs to retail investors, also reflects a collapse of confidence in rich country central banks’ enthusiasm for higher interest rates and governments’ interest in controlling large (and growing) deficits. Bloomberg suggests that the massive increase in the value of the global gold market is strengthening China’s effort to build up alternatives to the dollar, and Rajan agrees that alternatives to SWIFT are much more realistic now. Meanwhile, African economies, starting most visibly with Ghana, will confront even more difficult regulatory problems as the price of the metal, in local currency, is now nearly ten times what it was a decade ago.

“Cyber Resilience and State Capacity in West Africa: Lessons from the DDoS Surge”

Submitted by Hannah Krienke | Doctoral Fellow | Trust

NetScout Systems has published its latest global intelligence report, highlighting increased attacks on digital infrastructure across West Africa. The report reveals two important findings: first, the attacks were primarily carried out through distributed denial of service (DDoS), by disrupting digital services such as banking and e-commerce. Second, most of these disruptions are occurring in countries facing political instability, such as Mali. The correlation between Mali’s political instability and its cyber vulnerability, contrasted with Ghana’s 80% decline in attacks, demonstrates that digital resilience is also a function of institutional capacity to mitigate these attacks, not just technological investment.

The frequency and nature of these DDoS attacks may represent a shift in cyber threats. Unlike traditional hacking, which seeks to penetrate systems and extract valuable data, these disruptions are aimed solely at destroying the functionality of these digital infrastructures. The duration of these disruptions is striking, as these attacks have a twofold consequence, which is not just the immediate impact: the effect it has on business services, but rather what it exposes about the nature of state capacity. These attacks will then persist for hours due to a lack of defence mechanisms by the state that could include incident response capabilities, monitoring systems, and consequences for attackers. While a brief outage might be dismissed as a technical failure, when critical infrastructure remains under siege for hours, it becomes a public demonstration of state governance struggling to effectively secure and protect these infrastructures and their users.

“Gambling in South Africa”

R1.5 trillion turnover: Online gambling snares South Africa’s youth | The Citizen

Submitted by Laura Phillips | Senior Researcher | Trust

South Africa has a gambling problem. In mid-October the National Gambling Board delivered its 2024/2025 Annual Report to parliament, reporting that there has been a R1.5 trillion turnover in the past year. Online betting, casinos, and Limited Payout Machines - in that order - make up the bulk of the gambling industry’s profits, but this is only part of the story. Huge amounts, though it’s difficult to know how much, are also spent on illegal gambling, much of which happens online. Registered in the Caribbean, there’s been a mushrooming of online casinos that slip through the wide cracks in the South African gambling regulation. This, of course, is a worry for the tax man in South Africa, but it is equally concerning how much power over society legal betting operations have. As the Gambling Board emphasised in their report to parliament, it is time to start regulating, controlling, and possibly curbing gambling advertising in the country.

“In Gold we Trust: Gold breaks the $4000 barrier”

Gold Breaks $4,000 Barrier as Investors Seek Safety

Submitted by Tunde Okunoye | Doctoral Fellow | Trust

Amidst the global news frenzy about cryptocurrencies as a hedge against global financial instability, traditional stores of value such as gold have nonetheless remained relevant, even gaining in popularity. The price of the yellow metal has doubled in less than two years, as surging demand from central banks, investor fears over U.S. debt, the ongoing U.S. government shutdown, and new tariffs on imports announced by President Donald Trump push the metal to a record high.

This renewed demand for gold has been led by Central banks, especially, China, Turkey, and India, which have been major buyers. They have purchased around 1,000 tonnes of gold each year for the past three years to reduce their dependence on the U.S. dollar. It is perhaps also trivial to link this appetite for gold to the geopolitical tensions the countries have had with the United States. China, in its push to emerge as the next global superpower, and India in its insistence on Russian oil despite the U.S.’s disapproval. It is estimated that gold could reach $5,000 by the end of the year.

“Ghana’s National Service Authority (NSA) is in the spotlight again”

Prosecution yet to serve Osei Assibey Antwi with a hearing notice | Ghana News Agency

Submitted by Caroline King | Doctoral Fellow | Trust

Earlier this year, senior staff of the National Service Authority (NSA) faced major backlash and repercussions after it was revealed that ‘ghosts’ had been receiving payments through the scheme over multiple years (discussed in the May 2025 substack). It was reported at the time that the responsible people were to be charged in May 2025, but it seems that at least one of the most notorious people involved in these fraudulent activities has yet to be prosecuted. The NSA’s former Executive Director is scheduled to appear in court on 20th October 2025, although his legal team claims he has not received any kind of notice. He is charged with stealing, causing financial loss to the state, money laundering, as well as authorising payments to registered ghost names in the system. If this is not shocking enough, it is alleged that he transferred over GhC 8 million of the NSA’s funds to his personal e-zwich account – a digital biometrics-based infrastructure that is supposed to limit the possibility of this kind of fraud.

Further, the Deputy Executive Director defrauded the NSA by claiming goods and loans meant for NSA service personnel and funnelling it through multiple companies that she controlled, ultimately costing the state millions of GhC. This story is not new in Ghana; it has been unravelling since the beginning of 2025, but the slow processing of the accused is disheartening. Moreover, the role of e-zwich is concerning in all of this, as it raises questions about the security level of the FinTech. Nevertheless, the upcoming trial hopefully sends a signal to other government agencies that the new government intends to prosecute this type of behaviour.

“What IMF Debt Really Measures”

Submitted by Fatima Moolla | Doctoral Fellow | Trust

Eighty-six countries owe the International Monetary Fund a combined $162 billion, according to Al Jazeera. Africa accounts for more than a fifth of that total — led by Côte d’Ivoire ($4.2 billion), Kenya ($4.1 billion), Ghana ($3.6 billion), and Angola ($3.6 billion). These numbers are often used to signal financial distress or dependency. But what do they actually measure?

In reality, the size of a country’s IMF debt tells us less about its economic health than about the structure of its political economy — and the degree to which its fiscal choices are externally governed. The Fund’s loans come with conditions that reach deep into domestic policymaking: ceilings on public wages, subsidy reforms, the introduction of digital tax systems, and fiscal transparency measures that shape how governments spend, collect, and account for money. Kenya’s $4 billion facility, for example, reoriented the national budget toward IMF-approved austerity. Ghana’s programme did the same, recasting fiscal discipline as credibility.

The paradox is that small numbers can carry disproportionate influence. While $4 billion may seem modest compared to Argentina’s $57 billion bailout, the leverage attached to each African dollar is much higher. Conditionality functions less as financial oversight and more as a system of policy standardisation — a mechanism through which technocratic reforms are quietly globalised.

Meanwhile, a handful of African states — including Lesotho, Comoros, Eswatini, and Mali — have maintained minimal exposure to the IMF. Their limited borrowing offers short-term policy space, but it has not insulated them from internal pressures. These countries continue to grapple with slow growth, fragile fiscal bases, and rising domestic inequality. In the absence of external financing, governments often turn to opaque domestic borrowing or regional lenders, trading one form of constraint for another. Autonomy from the Fund, in this sense, is less a marker of resilience than a different configuration of vulnerability.

The IMF’s balance sheet, then, is less a financial ledger than a map of political trust and dependency. To owe the Fund is to be enrolled in a global infrastructure of surveillance and compliance; to avoid it is to operate outside that system, at the cost of isolation. Whether that’s resilience or vulnerability depends not on the size of the debt — but on who gets to define the rules of solvency in the first place.

“Legal Identity Across the Life Course: Gender, Registration, and the Politics of Digital Inclusion”

Submitted by Jonathan Klaaren | Professor | Law

A recent UN symposium held in Nairobi Kenya reviewed and considered routes towards achieving a number of sustainable developmental goals including that of legal identity. One of these goals was financial inclusion, a goal with near-universal support. Contestation emerges when specific routes towards pursuit of that goal are chosen and implemented. The symposium is worth noting and discussing here for emphasizing a gender perspective on investments into and capacity-building initiatives for bolstering extant national civil registration and vital statistics systems.

As the excellent background paper for this event explicitly argues: “Legal identity across the life course matters for gender equality and women’s empowerment. One’s civil status begins at birth and ends with death. Individuals may marry or divorce over the course of their lives. Civil registration provides documentary evidence of legal identity, family relationships, nationality and human rights.” The discussion at the symposium focused on making real choices and investments. Significantly, one view was that “there has been a disproportionate focus on strengthening birth and death registration systems in many countries, leaving much progress to be made in enhancing systems for registering marriage and divorce. Yet, marriage and divorce represent key life transition moments that have notable implications for the rights and welfare of women and girls. Universal registration of marriage and divorce is often neglected, but facilitates access to rights irrespective of sex or gender orientation.” Romesh Silva et al., The Life-Course Approach to CRVS: A Crucial Tool to Advance Gender Equality (2023).

The feminist aspect of this view can be justified in part pragmatically and with a focus on implementation (as contrasted with more purely rights-based Nora P Powell, Human Rights and Registration of Vital Events, no. 7, Technical Papers (International Institute for Vital Registration and Statistics, 1980) or historically-informed Simon Szreter, “The Right of Registration: Development, Identity Registration, and Social Security—A Historical Perspective,” World Development 35, no. 1 (2007): 67–86 arguments) through legal identity and its nexus with private property: ”A marriage certificate provides legal proof of marriage, which women can use to secure property and collect an inheritance when their spouse dies. Similarly, divorce registration allows both individuals to remarry, and provides a legal basis for the distribution of parental responsibilities at the end of a marriage.” Romesh Silva and Priscilla Idele, Making Everyone Count: Advancing Gender Equality and Women’s Empowerment through Inclusive Civil Registration and Vital Statistics (CRVS) Systems Nairobi, Kenya, Background Paper to the 4th Global CRVS and Gender Symposium (UNFPA, 2025), 4. The under-emphasis in the field on marriage and divorce registration – an emphasis which allows for gaps on capturing the mid-life transitions of individuals -- is reflected in the growing number of civil registration (and more) assessment tools current developed and deployed.

The above gender perspective can make a big difference in approaching one of the current day’s big topics – digital public infrastructure. As the authors note, “digitalization alone does not guarantee inclusivity or equity. In fact, poorly designed digital systems may deepen exclusion, especially for marginalized populations, sometimes resulting in litigation and court rulings on the legality of such exclusion from identity management systems.” (Silva and Idele, Making Everyone Count,10)

Trust in Transition is a Substack, by the Trust Project, exploring the intricate interplay between trust, finance, and societal evolution within the African context. This space serves as a lens into the fascinating dynamics of trust infrastructures, financial landscapes, and their transformative impact on Africa's economic pathways.

Wow, this edition really connects the dots in unexpected ways. The focus on trust infrastructure and digital IDs is so spot on; it's the bedrock for so much, even in AI developement.