Welcome to the One-Year Anniversary Edition of Trust in Transition!

This monthly newsletter, compiled by WISER scholars, is your gateway into finance, technology, and trust in Africa. Each month, the Substack features WiSER scholars unpacking the current events and stories shaping their research.

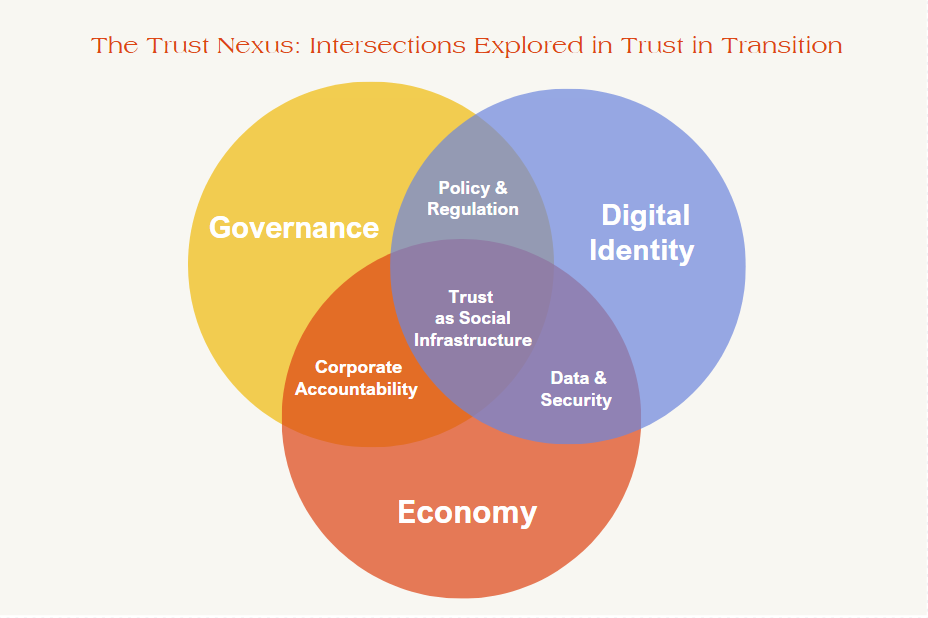

This edition of Trust in Transition reflects on a year of exploring the intersections of trust, technology, and governance. Highlights include a retrospective on the themes and insights that have defined our journey, alongside a Guest Feature on the rising prominence of facial biometrics in digital identity. This month’s WiSER Feature critically examines trust deficits in Ghana’s election processes, while other contributions tackle issues such as banking responsibility, digital identity in Africa, the erosion of trust in liberation movements, and the growing significance of cybersecurity. Each piece offers a fresh perspective on the dynamic role of trust in shaping political, social, and economic landscapes.

Inside This Edition

📅 Summer Recap

🌍 WiSER on the Move

🎉“Reflecting on a Year of “Trust in Transition” Fatima Moolla

🎤 Guest Feature: “Having Everyone in the Picture- Facial Biometrics headed for a Photo Finish” Sanjay Dharwadker

⭐ The WiSER Feature: “Why is there no trust in Ghana's election process?” Caroline King

✏️ Contributions:

In this edition, Wiser Trust scholars and affiliates are reading the following:

“New models of banking responsibility” Keith Breckenridge | Professor | Trust

“Africa: On the precipice of the global digital identity revolution” Raymond Onuoha | Postdoc Fellow | Trust

“Trump’s 2nd coming: A breakdown of Global Trust and Multilateralism?” Tunde Okunoye | Doctoral Fellow

“Trust as the new currency in the era of cybersecurity ?” Georges Eyenga | Postdoc Fellow | Trust

“Where is the Trust? Southern Africa’s loss of confidence in Liberation movements.” Hannah Krienke | Doctoral Fellow | Trust

“Banking Reforms and ‘Reputational Risk’” Laura Phillips | Senior Researcher | Trust

📖 Reading spotlight: Youssef Mnaili on Les Institutions Invisibles by Pierre Rosanvallon

Summer Recap 🗓️

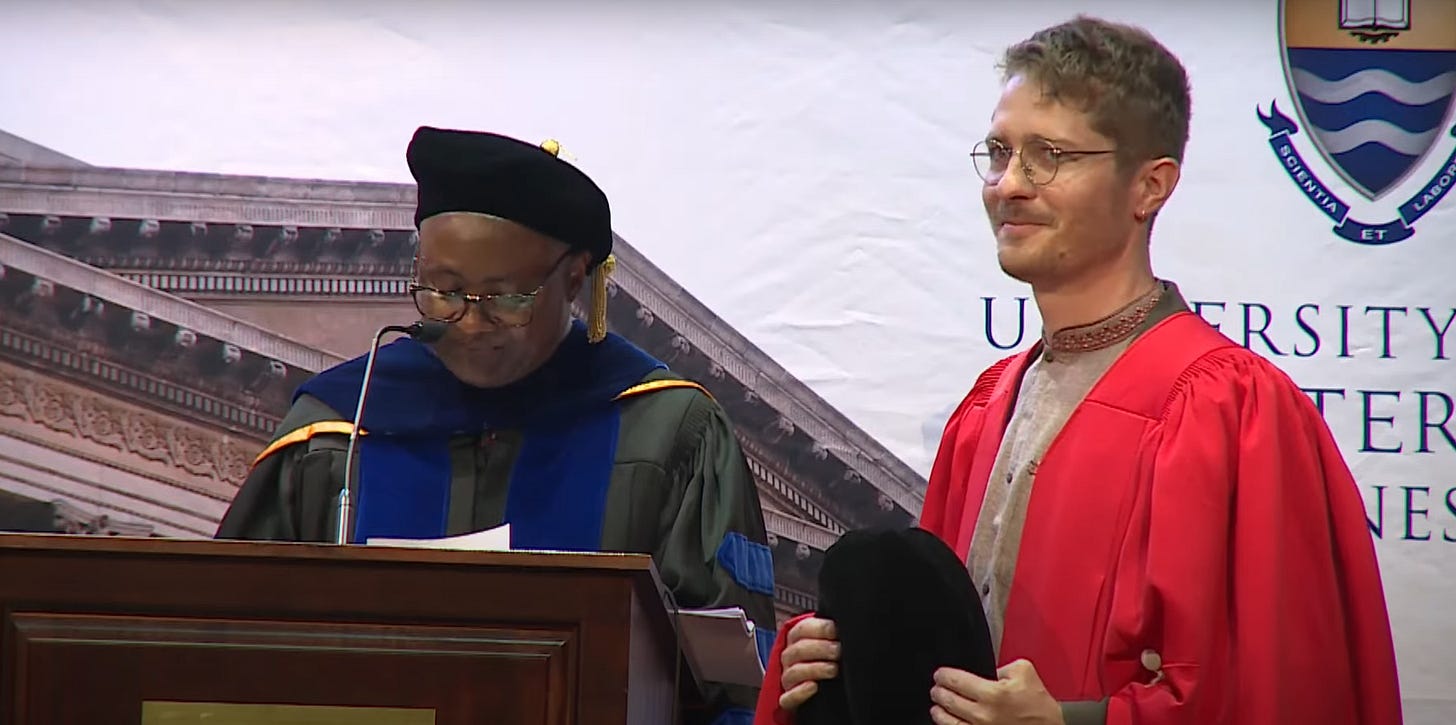

Congratulations to WiSERs own Dr Joel Pearson who received his PhD on the 9th of December 2024. Dr Pearson’s dissertation was titled “Three Axes of Rural Local Governance: A relational history of space, administration and economic extractivism in the Mogalakwena Local Municipality in Limpopo, South Africa (1948-2000)”

WiSER on the Move🌍

PhD Fellow Caroline King attended the lecture and workshop conducted by Prof. Jemima Pierre at the University of Ghana on 12–13 December 2024. She also participated in the Deutsche Welle (DW) videotaping at the University of Ghana in November, which focused on galamsey (illegal mining) and its effects on Ghana.

PhD Fellow Fatima Moolla completed her visiting PhD fellowship at Carnegie Mellon University Africa, hosted by the Upanzi Network in Kigali, Rwanda. During her fellowship, she conducted fieldwork for her research on land registration and digital public infrastructure.

Postdoctoral Fellow Youssef Mnaili attended the "Study Day on Palestine" organized by Maghreb Middle East area (MaMo) and Institut National des Langues et Cavilisations Orientales (CESSMA) in Paris on December 2, 2024. He presented on the bureaucracy of Israel's occupation and the settler movement, contributing to discussions on colonialism and resistance.

Postdoctoral Fellow, Dr Raymond Onuoha participated in the International Digital Dialogues Conference (IDDC) in Berlin, Germany. The conference convened over 100 selected delegates from the public and private sector, civil society and academia to stimulate an international dialogue on current digital policy issues.

In a 17 January 2025 webinar hosted by the Swiss research and policy organization CEP, WiSER researchers Raymond Onuoha and Jonathan Klaaren were part of a discussion on the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) and its digital trade protocol (DTP). Digital identity is part of the DTP – defined as “a set of unique and validated digital attributes or credentials for identifying a natural or juristic person”. The discussion highlighted several points. Fellow panelist Kholofelo Kugler highlighted that under the digital trade protocol, many African jurisdictions have reported the absence of international trade restrictions related to payments. This indicates that the payments sector is one where policy alignment across the continent may emerge relatively quickly. Beyleveld and Sucker have also highlighted the importance of incorporating competition rules into cross-border data flow regulation under the AfCFTA DTP to protect smaller competitors and ensure more equitable market access, thereby addressing economic disparities across the continent. Digital trade is fast becoming a significant topic for attention by policy actors including the African Competition Forum.

Reflecting on a Year of “Trust in Transition” 🎉

Fatima Moolla | PhD Fellow | Substack editor

After a year of publishing Trust in Transition, one thing is clear: trust is not an abstract concept—it’s an infrastructure. It’s built, eroded, contested, and reshaped in ways that define modern life. Our eleven editions have explored how trust functions across technology, governance, and corporate power, revealing its central role in shaping societies.

Trust as Infrastructure

From digital ID systems in Africa to mobile money networks, trust emerged as a foundational infrastructure—one that connects individuals to essential services. But as our contributors revealed, this infrastructure is far from neutral. It can enable inclusion or deepen exclusion. Moniepoint’s billion-dollar valuation and Nigeria’s SIM-NIN policy illustrated how trust-based systems unlock economic potential, while cases of data breaches and financial scams underscored how fragile digital trust can be.

Governance and the State-Citizen Relationship

Many stories probed trust’s uneasy relationship with the state. Contributions on Nigeria’s tax reforms, South Africa’s grey listing, and biometric ID projects in Cameroon showed how governments struggle to earn public trust. Far from being just technical fixes, these initiatives exposed how trust is often imposed from above—shaped by international pressures or political survival. This top-down approach frequently deepens citizen skepticism rather than alleviating it.

Corporate Power and Historical Echoes

Corporate dominance emerged as another key theme. In Echoes of the Mines: Elon Musk and the Legacy of Economic Extractivism, we followed along as scholars traced the historical links between South Africa’s mining economy and Silicon Valley’s monopolistic tech empires. This recurring story of extraction, control, and wealth concentration was mirrored in features on commodity traders, telecom fines in Zimbabwe, and the evolving role of fintech platforms. Trust in corporate actors often hinges on their ability to navigate regulatory landscapes while pursuing relentless profit.

The Future of Trust: A Shifting Battleground

Contributions on artificial intelligence, digital surveillance, and voter security emphasized trust’s shifting terrain. Trust isn’t static—it adapts, is contested, and even weaponized. AI-driven military campaigns, data-driven voter manipulation, and tech-enabled surveillance remind us that trust in the digital age is inherently precarious. Whose values shape these technologies? Who defines what’s trustworthy—and for whose benefit?

Over the past year, Trust in Transition has become a platform for exploring how trust operates in a world shaped by shifting power, technology, and policy. It’s a space for critical reflection on trust’s possibilities and limits. Trust isn’t guaranteed—it’s built, negotiated, and sometimes broken. Moving forward, our Substack will dive deeper into these themes, while also spotlighting upcoming events and discussions on our Trust Project page. Stay tuned as we continue to explore key questions like: Who builds trust? Who breaks it? And what happens when trust fails?

How do you Understand Trust?

The WiSER Feature 📝

Why is there no trust in Ghana's election process?

Caroline King | PhD Fellow

2024 was a super year for elections, with 72 countries voting on their government representation.[1] This includes Ghana, whose citizens voted on the 7th of December 2024. The country is considered a stable democracy, surrounded by Francophone countries and the Sahel region which has seen recent political changes that have the potential to affect democracies in West Africa.[2] Although Ghana has faced an economic crisis and a devaluation of its currency since 2022, the country's political stability remained intact so that the lead-up to the election date saw relative calmness. This sentiment could be observed on election day, where people could vote throughout the day until 5pm. After 5pm the ballots were publicly counted at the polling stations in front of anyone who wanted to observe. The number of votes for each candidate was called out, noted and signed off on by each party representative, and then the closed ballot boxes and signed forms were transported to the collation centers. At the collation centers the results were scanned and sent to the Election Commission's Office where the results were published. Although the counting process is publicly accessible, many Ghanaians were suspicious towards the authenticity of the results, especially at the collation centers, where there were both threats and in a few instances fatal violence reported. As an informal observer, I was quite surprised by the suspicion that Ghanaians seemed to have towards the election process, which made me wonder, how democratic Ghana is, if its citizens, although they are able to observe the whole process, do not believe that the Election Commission fairly carries out the election.

The perception that the Election Commission does not carry out fair elections might be attributed to a general mistrust that citizens have towards the state in Ghana. This mistrust has been growing in Ghana over the years, and is especially high during election years, as Afrobarometer survey data suggests.[3] But what has led to this mistrust in the Ghanaian state? As previously mentioned, the depreciation of the Ghanaian Cedi since 2022, and the economic hardship that followed have led to increased food and oil prices, without concomitant wage increases, leading many Ghanaians to the brink of ruin without any social security.[4] This downward trend has continued onward into 2025, without sufficient measures being taken by the Ghanaian government or the Central Bank.[5] Furthermore, a lack of transparency in how the Ghanaian government allocates funds also raises suspicion. This includes questions around the cost of the African Games that were held in 2024 in Ghana, as well as funds that were supposed to be used to improve public infrastructure in the country and dodgy procurement deals.[6] Moreover, interactions with state representatives in public offices or the police are often tainted by requests for bribe money, rather than a sense of security or trust to represent the state and protect its citizens. Afrobarometer confirms this perception, their survey done in 2021/2023 (Round 9) asked "How many of the following people [police] do you think are involved in corruption?" 29.6% of Ghanaians believed" all of them" were involved, and 35.3% believed "most of them" were involved in corruption. Only 2.8% believed "none of them" were corrupt, which could indicate that most Ghanaians have had interactions with police that involved a bribe or other corrupt activities in one form or another.[7] When asked about how the government is fighting corruption, Ghanaians also seem skeptical about their government's ability.

In Round 10 (2024/2025) of the Afrobarometer survey, 61.5% of Ghanaians said that the government is handling corruption in government "very badly,"[8] while only 2.7% believed the government was doing "very well." [9] This marks a sharp decline in trust compared to Round 8 (2019/2021), where 34.6% rated the government's efforts as "very bad," and 8.4% as "very good." Over the past three to four years (roughly a presidential term), the perception of the government’s ability to fight corruption has worsened significantly, with nearly 30% more participants now believing the government is handling this task "very badly." This trend reflects an increase in mistrust toward the presidency and the administration it leads.

In relation to the election commission and the government in general, Afrobarometer asked participants if they trust the Electoral Commission. In the 2021/2023 survey (Round 9) 39.7% of participants stated that they do "not trust them at all", and only 9.8% said they "trust the Electoral Commission a lot". 27.3% said they trust them "just a little" and 22.7% say they trust them "somewhat".[10] In the 2019/2021 survey (Round 8), Ghanaians were more trusting, where only 19.7% did "not trust the Electoral Commission at all". 23% trusted "just a little", 31% "somewhat" and 20.7% "a lot".[11] That means, within two years the Electoral Commission was perceived as 20% less trustworthy overall, with over 10% fewer Ghanaians trusting the Electoral Commission fully. This shift does indicate a decline of trust towards the Electoral Commission over time and might explain why Ghanaians were so suspicious towards them during this 2024 election.[12]

Overall this data suggests that trust in the Ghanaian state has been on the decline for a while, with a downward trend continuing. It also might explain some of the suspicion that Ghanaians displayed on the voting day, as most of them have been burned before by false promises made. As a new government has come into power, let's hope that promised improvements are held and new leadership is able to regain some of the trust lost, so that Ghana can remain in its position as one of the strongest democracies on the African continent.[13]

Guest Feature 🎤

Sanjay Dharwadker is the Senior Digital Identity Officer in the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) based in Copenhagen. He also works on global identity standards at ISO as well as the New technology Working Group (NTWG) and the Implementation and Capacity Building Working Group (ICBWG) of the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO).

His current focus areas include digital identity in the humanitarian space, civil registration, evidence of identity, data protection, biometrics and biographics. Sanjay Dharwadker has over three decades of experience in the field of identity and identification with assignments in Asia (1989 – 2004), Africa (2004 – 2014) and Europe (since 2014) which include working for leading technology companies, national governments, as well as the United Nations and the World Bank.

He is a participant at The Hague Colloquium on the future of legal identity (Bhalisa) and writes regularly on the subject. Sanjay is a member of the Crime Writers' Association (CWA) of the UK and published his first crime thriller "Diamond in my Palm" in 2019.

Having Everyone in the Picture

Facial Biometrics headed for a Photo Finish

For automated facial biometrics to have happened as it did, at the beginning of the twenty-first century, many diverse technologies and social circumstances needed to come together, which they did in serendipitous ways. There was the evolution of photography itself during much of the 1800s[14], its first use for photo ID, in 1876[15] at the Centennial exhibition, Philadelphia, and events like the Lody spy scandal[16] of 1914 involving USA, UK and Germany that hastened the mandatory use of photographs for passports.

Coining of the word “photograph” itself for an image captured by a camera is attributed to John Herschel (1792 – 1871) in c.1842 who, serendipity taking its strangest turn in the world of biometrics, was the father of William Herschel (1833 – 1917) the British civil servant in India who introduced fingerprints on legal documents (c. 1858) as a biometric identifier, for the first time in modern administrative history.

For further developments, all this needed to wait nearly a century, till computers and programming in the 1950s and 60s saw the advent of statistical pattern recognition, based on the work of Ronald Fisher[17]. All this came together for automated facial recognition in work done during the 1970s to the 90s[18], that continues today as mobile phones and artificial intelligence (AI) evolve.

Today, the state of the art of the technology is best found in texts[19] such as the 2011 Handbook on Facial Biometrics.

But by 2020, barely 20 years into the large-scale use of facial recognition, momentum against its use was also building up across various sections of society[20] while, the face was being standardized as the primary biometric for machine readable travel documents (ePassports) across the world[21] giving it a legitimacy and a platform for large-scale use across all United Nations member states. This had also helped build up a multi-billion-dollar industry around this technology.

The point of bringing all this up for discussion and reflection is simply this: Why is automated facial recognition important? What can it deliver? Why is it feared, and if at all, how can it be tamed and controlled, and ultimately harnessed only for the good for humanity?

Facial biometrics is easy in some ways. Unlike fingerprints and iris, it requires no special capture devices. Identity verification (one-to-one) can be done while ensuring privacy and data protection as is done at the Automatic Border Control (ABC) gates for international border crossing, where the facial image remains securely ensconced in the chip of the ePassport and there are no centralized databases involved. Another use is deduplication (one-to-many) that ensures uniqueness of an identity. This however needs to look at large biometric databases together, but where privacy needs to be built in through anonymization. However, facial images can be captured without the knowledge of individuals and subjected to large-scale surveillance, which gives the technology its double edge, coming with risks that legal frameworks seek to mitigate today. This is certainly a persisting challenge.

On the other hand, billions of individuals have already been photographed for their identity, for their ePassports, national identity, and other functional identity systems. The photographs are printed (black and white or colour) and stored digitally where they then become the means of “measuring” the likeness of a person.

For such measurement to be accurate, there are ISO standards in place, agreed upon by international experts, research scientists, industry and governments. These standards bring out the complexities of how a photographic portrait is transformed from an art and a craft into a digitally measurable and comparable artefact.

One such example is the ISO/IEC 39794-5:2019 - Information technology — Extensible biometric data interchange formats Part 5: Face image data[22].

This standard makes significant departures from earlier ones by incorporating a more comprehensive understanding of factors such as illumination, background, distance (selfie vs. studio, for example), pose and dimensions. The standard also provides for metadata such as gender, eye colour, hair colour, subject height, expression, pose angle and landmarks. More importantly, it breaks away from the old racial stereotypes of skin-tone, like the von Luschan scale[23] (early 20th century) and Fitzpatrick[24] (1975) to be replaced by more robust developments in spectrophotometry that are systematically embodied in yet other standards such as those for colorimetry[25] (IEC 61966-8) and for illuminants[26] (ISO/IEC 11664-2).

On the digital side, the standard moves on from the older tagged binary data format (ASN.1) to the more universal textual data format (XML), making them more universally interoperable.

As digital practices proliferate across documents and their applications (passports, drivers licenses, national ID cards etc.) the need for standardization and interoperability have also increased. This standard therefore provides for a generic face image data format for automated face biometric verification (one-to-one comparison), identification (one-to-many comparison), as well as human verification with sufficient detail.

It also addresses 2D as well as 3D facial images, landmarks as well as statistical quality parameters.

Despite being extremely contemporary in its approach, it cannot escape references to older studies, for example the Frankfurt am Main Agreement of 1882 that standardized the essential schema of the skull in anthropometric terms on a horizontal plane. Digital facial images and matching techniques today, depend significantly on such formulations and the ultimate determination of facial image quality (such as having 80 – 240 pixels between eyeballs) are found to be derived from all this.

To conclude, as both, the technology of facial biometrics as well as the social and legal concerns around these evolve, it is difficult to foresee photographic portraits, either in print or in digital form, be dispensed with altogether.

In the least, these would continue to be accessories to identity documents. But on the other hand, a comprehensive photographic record could hugely complement existing current practices of civil registration that are in the written form and continue to exclude nearly an eighth of the world’s ever- expanding population. However, how this could come about and what it could mean, remains to be seen.

✏️ Contributions:

“New models of banking responsibility”

Submitted by Keith Breckenridge | Professor | Trust

Earlier this month a bill from the Singaporean parliament came into force allowing the police to take control of the bank accounts of customers they have “reason to believe” may be about to participate in a scam. The law is a response to the growing persuasiveness and scale of bank transfer scams, which increasingly target old people over long periods of time and frequently involve very large amounts of money. In the first half of 2024, nearly $300 million was stolen from Singaporean bank customers. Similar changes are underway in the United Kingdom where the payment system regulator now requires banks to absorb up to £85,000 of the losses involved in so-called authorised push payment frauds. Here, again, the amounts involved are very large, with nearly £600 million stolen in the first half of 2024. Some of the UK banks have begun to argue that Meta (owner of Facebook and WhatsApp, medium of over 70% of the scams) should share liability for the payments. All of this represents an important shift in the long-settled principles of the common law of banking liability.

“Africa: On the precipice of the global digital identity revolution”

Submitted by Raymond Onuoha | Postdoc Fellow | Trust

Unlocking Africa's Digital Identity Potential

Nearly 1 billion people globally lack access to reliable identity systems, hindering their access to essential services and costing the economy billions in lost productivity. In Africa, over 500 million individuals remain without official identification, exacerbating inequality and limiting economic opportunities. This presents a unique chance for Africa to lead a transformative digital identity revolution.

In this piece, Digital Consultant - Ott Sarv, indicates that by adopting a unified digital identity ecosystem—integrating robust Civil Registration and Vital Statistics (CRVS) systems, biometric authentication, and interoperable frameworks—Africa can redefine how identities are managed. This approach empowers individuals to access financial services, start businesses, participate in civic processes, and manage personal data securely. Why should we care? Digital identity is the foundation of inclusive growth in the digital age. Africa's young, tech-savvy population and rapid adoption of mobile technology position it to leapfrog legacy systems and set a global benchmark. The benefits are immense: enhanced financial inclusion, economic empowerment, efficient service delivery, and regional integration.

However, success hinges on overcoming challenges like fragmented systems, cybersecurity risks, and trust deficits. By prioritizing governance, fostering regional collaboration, and embracing inclusive, scalable technologies, Africa can build resilient systems tailored to its unique context. This is more than a technological aspiration—it’s a pathway to socioeconomic transformation, ensuring every African is recognized, empowered, and included in a rapidly evolving digital world. The continent has the vision and potential to lead the global digital identity revolution, shaping a future where no one is left behind.

“Trump’s 2nd coming: A breakdown of Global Trust and Multilateralism?”

Submitted by Tunde Okunoye | Doctoral Fellow

Multilateralism Can Survive Trump

This week heralds the beginning of the 2nd Presidential term of Donald Trump as the leader of the United States of America (USA). Even weeks to his inauguration, political tremors have been felt as near as Canada, Greenland, Mexico; and as far as the United Kingdom (UK) and China. Trump has indicated he would prefer to see Canada as the 51st state of the USA, has expressed his interest in annexing Greenland using “all options on the table”, and has threatened huge tariffs on Mexico. The hitherto special relationship between the USA and the UK is under strain given the overt political support the UK Labour-led government gave the Democrats in the last USA election. Meanwhile, China only expects continued hostility from the Trump administration – spilling over from his first term in office. It is also certain that NATO and the European Union are not particularly enthusiastic about Trump’s return.

Trump’s return to power in the USA despite not being desired by many parts of the world only serves as a reminder that all politics is local. Whatever the world thinks, a decisive majority of Americans have judged and decided that a 2nd Trump term is in their best interests.

“Trust as the new currency in the era of cybersecurity ?”

2025 crucial for cybersecurity

This op-ed by Rizal Raoul Reyes highlights the importance of trust in shaping cybersecurity strategies in the economic world, in response to the growing threats fueled by artificial intelligence (AI). According to Simon Green of Palo Alto Networks, organizations must abandon fragmented approaches and adopt unified and transparent platforms to build adaptive and resilient defenses. Trust emerges here as an "essential currency," crucial for maintaining organizational resilience and safeguarding reputation against sophisticated threats such as deepfakes and quantum attacks. A secure architecture, combined with transparency in the use of AI, is deemed necessary to establish this trust among stakeholders.

While the text rightly emphasizes the significance of trust as a pillar of cybersecurity strategies, it remains superficial on two key aspects. First, it does not sufficiently clarify how organizations can ensure "trustworthy" AI in the face of complex challenges like data protection and algorithmic biases. Second, the role of states and regulators in establishing robust ethical and legal frameworks is underexplored. Finally, the discourse, driven by an industry actor, may reflect a commercial interest in promoting unified platforms without critically addressing the potential implications of concentrating solutions among a limited number of providers.

“Where is the Trust? Southern Africa’s loss of confidence in Liberation movements.”

Submitted by Hannah Krienke | Doctoral Fellow | Trust

Southern Africa’s liberation movements have lost their political mojo | Opinions | Al Jazeera

The article above is one of many that have been written in response to the winds of change sweeping through liberation parties across southern Africa. Electoral setbacks for parties like the BDP in Botswana, FRELIMO in Mozambique, and ANC in South Africa are a stark reminder that these parties, once revered for their pivotal roles in achieving independence are now grappling with growing public discontent. This discontent is fuelled by a confluence of factors including rampant corruption, economic mismanagement and a profound failure to address the evolving needs of their citizens. This erosion of public trust vividly manifested in declining voter turnout and the rise of opposition parties, particularly exemplified by the recent change in government in Botswana with Umbrella for Democratic Change (UDC) defeating the BDP in a landslide win that has been in power for over sixty years signifying a fundamental shift in public perception.

Peter Ekeh, in his seminal work "Colonialism and the Two Publics in Africa," observed that African bourgeois ideologies evolved to serve two goals: firstly, to displace colonial rule and secondly to legitimise the rule of the newly established African elite by consolidating absolute power and control. This observation resonates with the trajectory of many liberation movements, suggesting that their initial focus on anti-colonial struggle may have gradually shifted towards prioritizing the maintenance of power and the interests of the ruling class over the fulfilment of the broader public good. This shift characterised by a pronounced focus on self-enrichment and the consolidation of power has inevitably undermined public trust and contributed significantly to their declining influence.

The decline in trust in liberation movements has profound implications for the broader trust infrastructure across southern Africa. The erosion of public trust in elected leaders and the institutions they represent erodes the foundation of a functioning democracy leading to decreased civic engagement, a rise in social unrest and the weakening of crucial institutions such as the judiciary and the media. This in turn damages the fabric of social cohesion hindering collaborative efforts to address shared challenges exacerbating existing social divisions.

“Banking Reforms and ‘Reputational Risk’”

Submitted by Laura Phillips | Senior Research | Trust

FNB closes bank accounts of dodgy lottery-funded “activist”

Lost in the multiple sensational headlines in South Africa’s newspapers, is the story of Tebogo Sithathu whose bank account was recently closed by FNB. As reported in GroundUp, Sithathu is currently under investigation by the SIU for his involvement in suspicious grants by the Lottery Commission. Late in 2024 Sithathu apparently received a letter from FNB explaining that “having considered all aspects, we elected to terminate your banking relationship because, in our view, a continued relationship may expose the bank to reputational and business risk…” Sithathu went public about this on social media, suggesting that he – along with others such as the Guptas and Iqbal Surve – have been victims of “[the] weaponisation of reputational risk.” Whether he will take the case to the Banking Ombudsman is unclear but, as GroundUp has experienced, he is no stranger to appealing to the courts.

Invisible Institutions (trust, authority and legitimacy)

Youssef Mnaili | Postdoc Fellow

I am currently reading Les Institutions Invisibles by Pierre Rosanvallon (Seuil, 2024). His central argument is compelling: institutions are not merely the formal structures we typically associate with the term—such as schools, armies, and governments—but also the invisible forces that enable society to function, regulate itself, and project a vision for the future. These invisible institutions underpin the quality of relationships between individuals and between individuals and formal institutions, making it possible for societies to endure and evolve. Rosanvallon identifies three key invisible institutions: trust, authority, and legitimacy. These coexist with formal institutions, but unlike the latter—governed by leaders, hierarchies, and bureaucratic processes—invisible institutions operate beneath the surface, shaping the very fabric of social cohesion and interaction.

Rosanvallon argues that trust is the foundation upon which all relationships—both interpersonal and institutional—are built. It enables agreements to hold even in the absence of legal enforcement. While trust often originates within familial or local circles, its real societal power lies in its extension to relationships between distant or unfamiliar individuals. He terms this “real trust” (p. 12), distinguishing it from the localized, immediate trust that exists within close-knit communities.

Historically, trust has been vital to commerce. Rosanvallon traces its roots back to Aristotle, who, in The Constitution of Athens, described how inspectors and commissions in ancient Athens—such as the agoranomes (market regulators) and metronomes (guardians of weights and measures)—ensured fair trade by providing visible proofs of honesty. Similarly, in ancient Rome, the concept of fides (distinct from faith) formed the moral backbone of social life, emphasizing the fulfillment of oaths and commitments. Trust reduced uncertainty, simplified complex interactions, and facilitated economic and social expansion. (This observation may not feel particularly novel to the WISER trust seminar fellows.)

Authority, in Rosanvallon’s view, differs fundamentally from power. While power relies on coercion and the ability to enforce, authority imposes itself naturally, offering guidance and a sense of direction that is recognized and accepted without force. In this sense, authority represents the presence of society within the individual, shaping behavior and fostering order without the need for explicit commands.

Similarly, legitimacy stands apart from legality. While legality depends on adherence to procedures (e.g., elections or institutional processes), legitimacy is rooted in the collective sense that an individual or institution acts in the general interest. It is a moral dimension grounded in shared values and consensus, which cannot be imposed from above but must be recognized from below.

What makes these institutions invisible is their bottom-up nature. Unlike formal institutions, which function through top-down organization and coercion, invisible institutions emerge from the collective practices and interactions of individuals. Trust, authority, and legitimacy are all recognized and sustained from below. They cannot be commanded; they must be earned and cultivated.

Rosanvallon uses this framework to examine the limits of public power. A government lacking trust, authority, or legitimacy—even if it controls the police, Parliament, or other formal structures—will ultimately fail to govern effectively. Invisible institutions are the underground forces that bind society together, shaping the quality of relationships and creating the conditions for social stability and progress.

While Rosanvallon offers an engaging synthesis of ideas on trust, authority, and legitimacy, much of the discussion will feel familiar to readers well-versed in the literature on trust (e.g., Luhmann, Simmel). His innovation lies in connecting these three concepts into a unified framework for understanding invisible institutions. For newcomers to the subject, the book provides valuable insights. However, for those who have followed the trust seminar closely, it offers little that is genuinely new.

References

[1] https://www.undp.org/super-year-elections

[2] https://www.worldbank.org/en/country/ghana/overview

[3] https://www.afrobarometer.org/online-data-analysis/, Ghana, Round 10, Round 8, President, Trust.

[4] https://www.trade.gov/market-intelligence/ghana-currency-depreciation.

[6] https://citinewsroom.com/2024/08/group-petitions-osp-to-probe-245m-expenditure-for-all-african-games/#google_vignette; https://citinewsroom.com/2023/07/sky-train-project-2m-payment-was-made-by-giif-not-railways-ministry-joe-ghartey/; https://www.africanews.com/2019/08/22/ghana-s-head-of-public-procurement-suspended-for-selling-contracts//

[7] https://www.afrobarometer.org/online-data-analysis/, Round 9, Trust, Police.

[8] https://www.afrobarometer.org/online-data-analysis/, Round 10, Corruption, Government.

[9] https://www.afrobarometer.org/online-data-analysis/, Round 8, Corruption, Government.

[10] https://www.afrobarometer.org/online-data-analysis/, Round 9, Trust, Electoral Commission.

[11] https://www.afrobarometer.org/online-data-analysis/, Round 8, Trust, Electoral Commission.

[12] Maerz, S. F., Edgell, A. B., Wilson, M. C., Hellmeier, S., & Lindberg, S. I. (2024). Episodes of regime transformation. Journal of Peace Research, 61(6), 967-984. https://doi.org/10.1177/00223433231168192.

[13] https://www.journalofdemocracy.org/online-exclusive/why-ghanas-election-matters-across-africa/

[14] The History of Photography: From 1839 to the Present Paperback – January 1, 1982, by Beaumont Newhall (Photographer) https://www.amazon.com/History-Photography-1839-Present/dp/0870703811

[15] Hall, Roger; Dodds, Gordon; Triggs, Stanley (1993). The World of William Notman. David R. Godine. ISBN 978-0-87923-939-8. Retrieved 15 October 2018.

[16] Spies of the Kaiser, Palgrave MacMillan, 2004. Thomas Boghardt is a senior historian at the US Army Center of Military History. Prior to this post, he served as the historian at the International Spy Museum in Washington, D.C., and, formerly, as a Thyssen fellow at Georgetown University. He studied at Oxford University, St. Antony's College, where he received Ph.D. in European History in 1998.

[17] Owen, A. R. G. (1962). "An appreciation for the Life and Work of Sir Ronald Aylmer Fisher". Journal of the Royal Statistical Society. Series D (The Statistician) Vol. 12, No. 4 (1962), pp. 313-319 (7 pages) Published By: Wiley

[18] Kanade, Takeo, Computer Recognition of Human Faces, 1977, Springer Basel AG and the work of The FERET program started in September of 1993, with Dr. P. Jonathon Phillips, Army Research Laboratory, Adelphi, Maryland, serving as technical agent.

[19] Li, Stan Z and Jain, Anil K, Handbook of Face Recognition, 2011, Springer.

[20] Police surveillance and facial recognition: Why data privacy is imperative for communities of color Nicol Turner Lee and Caitlin Chin-Rothmann, Tuesday April 12, 2022, Brookings. This is one of many examples.

[21] Doc 9303 Machine Readable Travel Documents, Part 9: Deployment of Biometric Identification, 8th Edition, 2021 and Electronic Storage of Data in MRTDs. https://www.icao.int/publications/documents/9303_p9_cons_en.pdf

[22] https://www.iso.org/standard/72156.html and https://www.icao.int/Security/FAL/TRIP/PublishingImages/Pages/Publications/ICAO%20TR%20-%2039794-5%20eMRTD%20Application%20Profile.pdf

[23] Please see graphic at https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Category:Von_Luschan%27s_chromatic_scale

[24] Please see graphic at https://web.archive.org/web/20160331085655/http://www.arpansa.gov.au///pubs/RadiationProtection/FitzpatrickSkinType.pdf

[25] https://webstore.iec.ch/en/publication/26886

[26] https://www.iso.org/standard/77215.html

Trust in Transition is a Substack, by the Trust Project, exploring the intricate interplay between trust, finance, and societal evolution within the African context. This space serves as a lens into the fascinating dynamics of trust infrastructures, financial landscapes, and their transformative impact on Africa's economic pathways.